Kyosumi Maru

During my diving holiday of a lifetime in Truk Lagoon I found a rusty bike in a Japanese WW2 shipwreck which prompted me to consider the question, how have bicycles been used in war?

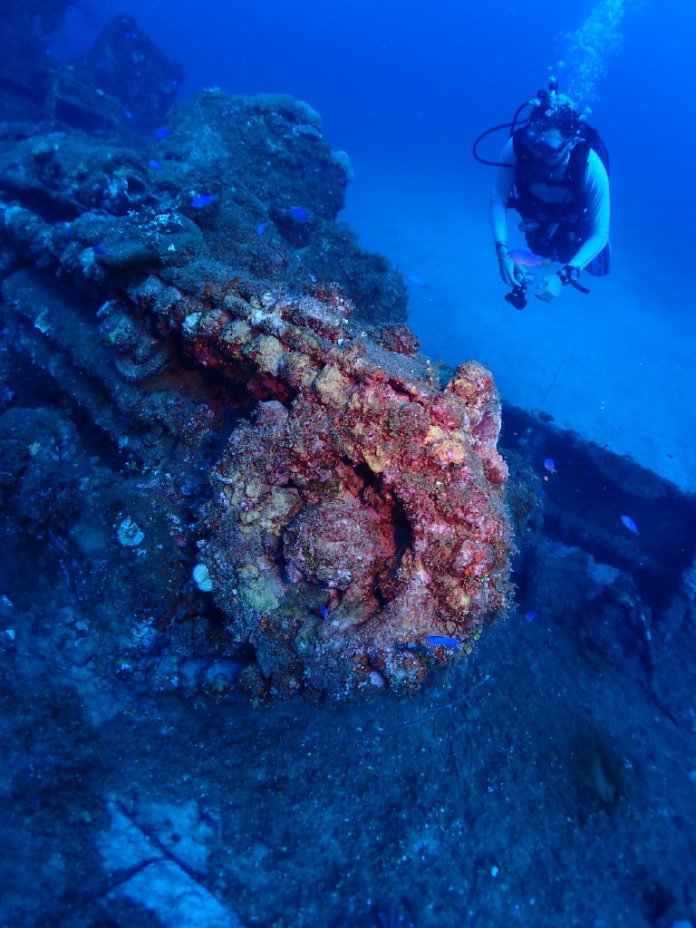

I was diving in the Pacific Ocean in the natural harbour and former Japanese naval base know as Truk or Chuuk Lagoon, part of the Federal States of Micronesia. The American navy attacked it in February 1944 with hundreds of planes launched from aircraft carriers and sank about fifty, mainly merchant ship. There are a few bicycles on these wrecks including this one on the Kiyosumi Maru.

As I looked to answer my question, I came across a fascinating and enjoyable book by Jim Fitzpatrick called the Bicycle in Wartime: An illustrated History.

Soon after the bicycle was invented, some hoped that it would play a key role in replacing the horse. It was quickly realised that the bicycle was not a straight swap for the horse, so bicycle charges with lances were abandoned for the more sensible opportunity of making troops more mobile. Fitzpatrick describes incredible training feats by European and American soldiers covering enormous distances with bikes laden with equipment. The reality is that, despite many miles cycled and strange bicycle contraptions created, the tank has replaced the horse and the bicycle has taken on a supporting role.

The bicycle first featured in the Boer War helping couriers and messengers. There were some combat units using bicycles in the First World War but again its usefulness was to aid couriers.

In the Second World War, the bicycle took on a combat role helping the German troops keep up with the tanks on their Blitzkrieg across Europe and Russia, the French Resistance to get around more freely and parachute troops, with folding bikes, to get to their objectives. Overall, the impact of the bicycle was useful but nowhere significant.

There have however been two times that the bicycle played a key role.

In December 1941, the Japanese invading army swept through the Malayan peninsular overwhelming British forces to capture Singapore. Through careful reconnaissance before the war, the Japanese commander Colonel Masanobu Tsuji realised that there was a perfect opportunity for war on a bicycle. There was a network of good roads and jungle paths built by the British to service the rubber plantations but the key was an abundance of local bicycles that were commandeered (stolen) by the Japanese infantry. This Blitzkrieg on bicycles was well planned and executed.

Tsuji’s tactic was to have mobile infantry units on bicycles supported by tanks and backed up by trucks carrying supplies. Each division had about 6,000 troops on bicycles. Each cyclist carried upwards of 65 pounds on his bike as well as a rifle or machine gun. They traveled in units of 40 to 50 soldiers riding four abreast. Whenever they met resistance they dismounted and fought on foot. If a bridge was blown up, a makeshift one was put in its place and the bicycles wheeled over. They pressed on relentlessly.

Up to 50,000 troops on bicycles covered 600 miles in seventy days a month quicker than Tsuji had planned. This remains the only example where bicycles were the main mode of transport for the whole army.

As the military historian John Keegan described, “the principal reasons for the defeat, in virtually every assessment, were the Japanese soldiers’s speed, tenacity and mobility. Although outnumbered two to one, they grabbed local trucks, cars, and bicycles as they went, and used fishing boats along the coast as well, both to push forward, and to skirt around to the sides and rear of retreating British and allied forces. When considered collectively, most comments upon the nature and rapidity of the advance point to the bicycle as the crucial transport element. It enabled the Japanese infantry to keep up an unrelenting pace not possible on foot. Numerous on-the-spot accounts noted that the cyclists were routinely well ahead of their tank and motorized support. In contrast to the European proving ground, the Malayan blitzkrieg was spearheaded by bicycles, followed by tanks.”

And Colonel Masanobu Tsuji said more succinctly in Singapore: The Japanese Story

“Even the long-legged Englishmen could not escape our troops on bicycles”

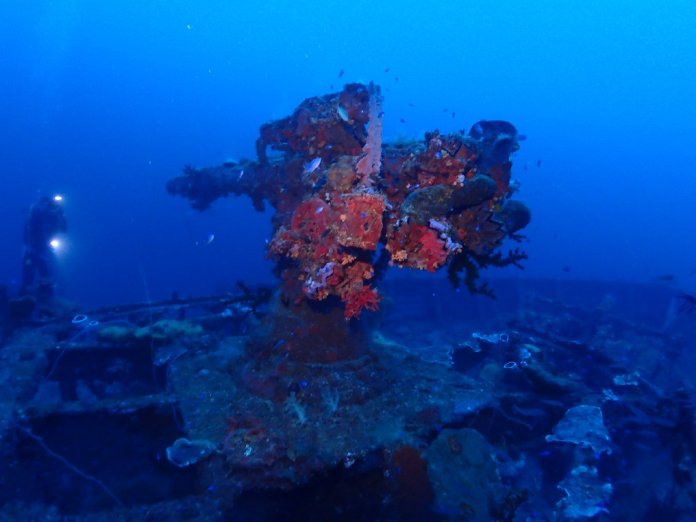

Japanese Light Tank on San Francisco Maru

The Vietnam War was also won by the bicycle, not by troops on bikes but by civilians using them to carry supplies. The key figure militarily was Vo Nguyen Giap. He developed the technique of many small scale actions, no single one being important, but cumulatively raising the enemy’s anxiety level and destroying his self confidence. Giap proved a genius at logistics, able to “move men and supplies around a battlefield far faster than anyone had any right to expect,” and learned how to work with villagers without being betrayed by them. In a prolonged struggle during which it was not always certain who was on who’s side, that was no small talent.

Bicycles played a key role in this logistics effort. They were strengthened and then loaded up with as much as 200 kilos of supplies. Often the saddle was taken off and replaced with a stick in the seat post to help pushing and steering was accomplished with another stick lashed to the handle bars. These two wheeled “pack-horses” were pushed through the jungle by local villagers.

In the First Indochina War against the French, they lost nearly 100,000 troops, with another 200,000 bogged down, in a nine year war. As the war due to a close, they decided to take a stand in Dien Bien Phu a purpose built fortress in the jungle blocking a key supply route for the Vietnamese.

Unknown to the French, a massive well equipped Vietnamese army was assembled over over months and surrounded them undetected. When the battle started, the French could not believe how much heavy weaponry, equipment and materials had been moved stealthily into place, mainly on bicycles, and quickly surrendered.

The Journalist Bernard Fall toured much of Vietnam on a bicycle during the war He attempted to calculate the tonnage moved by the Vietnamese logistics system. He did not include figures for supplies of local Vietnamese origin, but concluded that from China alone, some 8,300 tons were shipped to Dien Bien Phu, including petroleum products, ammunition, spare weapons, and rice. The immense amount of material that was moved by human energy was simply not anticipated by the French. The overall supply system was aptly characterized as a “human serpent” that came up from the plains and wrapped its coils around the French garrison.

In the Second Indochina War, the Americans knew better than to ask the French for advice. They had technology, helicopters, tanks etc but they underestimated the challenges of logistics and the power of thousands of civilians moving supplies on bicycles. One of these supply routes was the Ho Chi Minh Trail. It became the most critical and famous transport link of the war. It was a network of paths, roads, streams, and rivers running down the spine of the Annamite mountain chain of eastern Laos, through some of the most inhospitable terrain. In some places it was impossible even to push bicycles. Over the years the road was improved motorbikes began to replace bicycles from about 1970 and, in some places the road was widened so that trucks could be used. It is remarkable that the Americans failed to close this trail that it is estimated one million people traveled along during the war.

The bicycle has probably had its time on the Battle Field. The chapter closed when the last bicycle troops in Switzerland and their units were disbanded in the early 2000s. A recent news report suggested that the Swiss want to re-introduce bicycles to improve the fitness of their troops.

The bicycle will still have its place in war, however, as a way for troops and sailors to get around their bases, airfields or ports. I am sure that the bicycle I found on the Kiyosumi was used in this way. So in warfare that is increasingly dominated by drones and machines, the bicycle may not be on the front line but drone pilots may still use them to get to their cockpits and mechanics on the airfields that launch the drones.

There was a lot more to see than bicycles in Truk Lagoon….

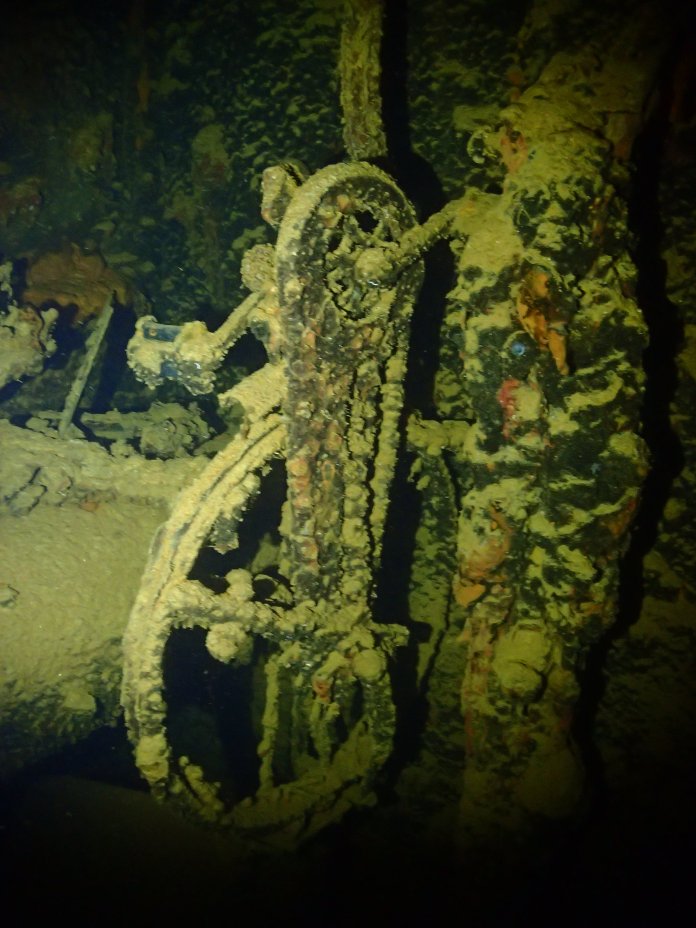

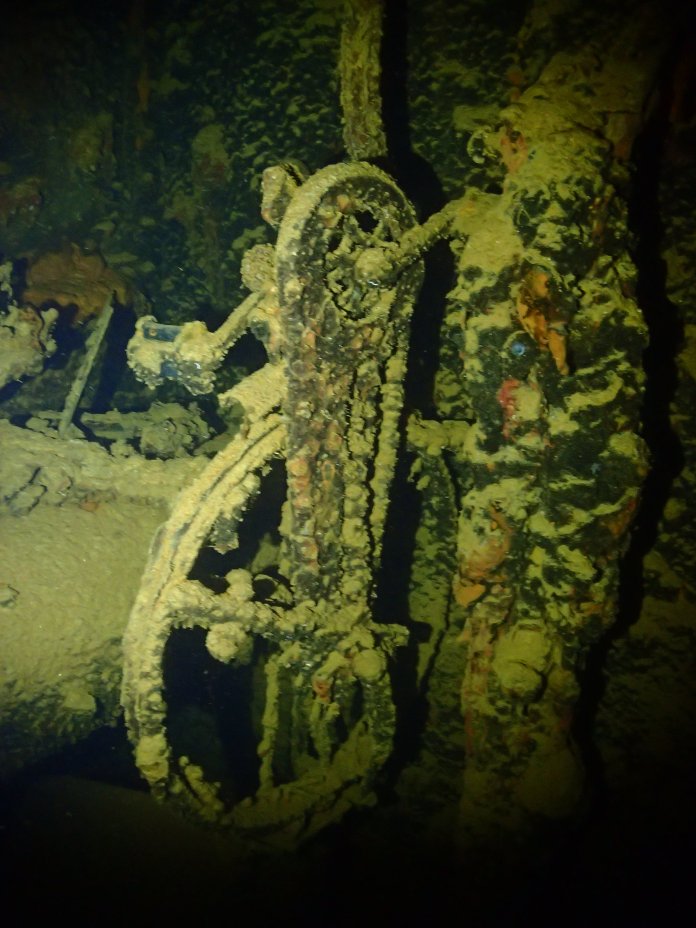

The Bridge of the Nippo Maru

Twin engined Japanese Bomb known as “Betty” Bomber